Why Not UBI?

Critiques of UBI include its cost and labor market effects, which could have broader effects on the economy; potential disruption to households who could lose existing benefits or pay more in taxes; and its focus on cash over healthcare, education, infrastructure, and jobs programs.

UBI would be expensive

The gross cost of providing a UBI of $1,000 per month to every person in the United States would be $4 trillion per year; limiting to adults would cost $3.1 trillion. For comparison:

- GDP is $21 trillion

- U.S. federal revenues total $3.5 trillion

- The current annual budget deficit is $896 billion

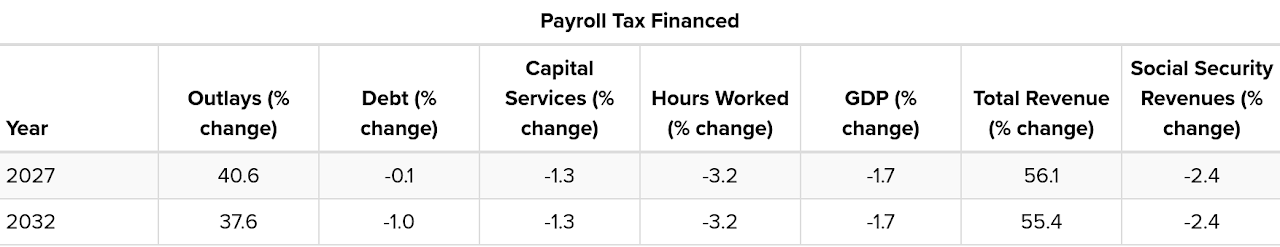

- The annual defense budget is $686 billion Paying for this, either with deficit spending or new taxes, can reduce economic growth. For example, in their 2018 analysis of a $500 per month per adult UBI, the Penn-Wharton Budget Model found that funding UBI through a payroll tax would reduce GDP by 1.7 percent in the first 10 years:

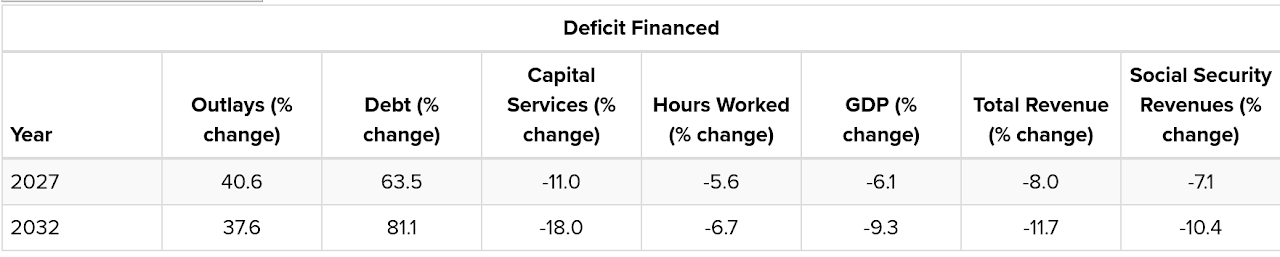

They also found that deficit-financing the cost would reduce GDP by 6.1 percent in the first 10 years:

Certain UBI policies could leave people worse off

Poverty researchers are concerned about the effects of spreading the budgets of means-tested programs across the population with UBI. Greenstein (2019) writes, “the increase in poverty and hardship would be very large” if the U.S. enacted a UBI funded solely by replacing means-tested programs. Hoynes and Rothstein (2018) also conclude that “replacing existing anti-poverty programs with a UBI would be highly regressive, unless substantial additional funds were put in.”

A UBI that also raises money through new taxes is also likely to leave some people worse off by reducing income after taxes and transfers. If a UBI policy has macroeconomic costs, those too would be felt by households.

UBI could reduce focus on other government programs

Social programs that improve health, education, and infrastructure may not be easily replaced with cash grants to households. If a UBI replaces any of these programs, as Murray (2006) proposed for Medicare and Medicaid, society could be worse off by underinvesting in these communal services. But even if UBI doesn’t explicitly replace these programs, it can shift the focus from investing marginal government dollars in services to expanding the UBI.

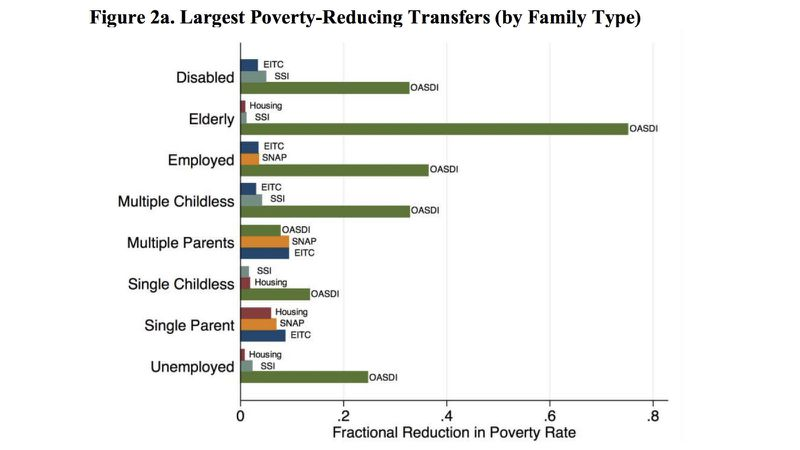

Existing assistance programs have also been relatively effective. Meyer and Wu (2018) find that Social Security (OASDI), EITC, and SNAP have cut poverty substantially across family types.

Antipoverty advocates may worry that emphasis on UBI could jeopardize these programs.